By Joel Schalit

When it comes to elections, all Torino neighbourhoods are the same.

Adverts featuring aspiring candidates appear on billboards several months in advance and rotate between the parties every few weeks.

Some areas have more billboard space than others, and political advertising is always present on public transit—in metro stations and on buses.

Most of the ads are indistinguishable. Whether left or right, candidates' faces tend to figure prominently, as though they’re supposed to communicate a specific ideology.

As a migrant, I’m more prone to reading them this way because I am not familiar with the politicians and because Italian is not my first language.

In and out of the country since I was a child, it’s not a new experience. My memory of Italian election advertising goes back to the early 1970s, when my father worked in Genoa.

Barely able to read to read in any language, I still have faint recollections of Italian Communist Party (PCI) billboards and the visage of former party chief Enrico Berlinguer.

Nothing could be more different than today, especially in our neighbourhood in southern Torino, which has been plastered with messaging from centre-right to far-right entities.

Not just from political parties but extremist groups that have always been visible in our neighbourhood—but not like today, emboldened as they may be by Giorgia Meloni’s leadership.

Indeed, the line between conservative and fascist appears increasingly blurred in contexts like this, where there has been little to no leftwing election advertising.

The reactionary continuum feels particularly out of place given its contrast with our neighbours. Most days, when I leave the flat, the first language I hear on the street is Arabic.

The greengrocer on our ground floor is Moroccan, and we speak to each other in French. Immediately across the street is a Filipino Pentecostal church, whose services are in English.

If I walk up to the corner, I’ll see a Romanian pasticceria to my left. If I turn right, I’ll pass a Bangladeshi night shop, followed by a barber with Chinese signage and a Tunisian kebab place.

It wouldn’t be so bad if the rightwing advertisements weren’t being commissioned by parties openly hostile to immigration. But they are. And everyone knows it.

It’s tough to ignore them in such diverse contexts. Even when they don’t say anything in particular, the ads instil a feeling of instability, as though our community could vanish in an instant.

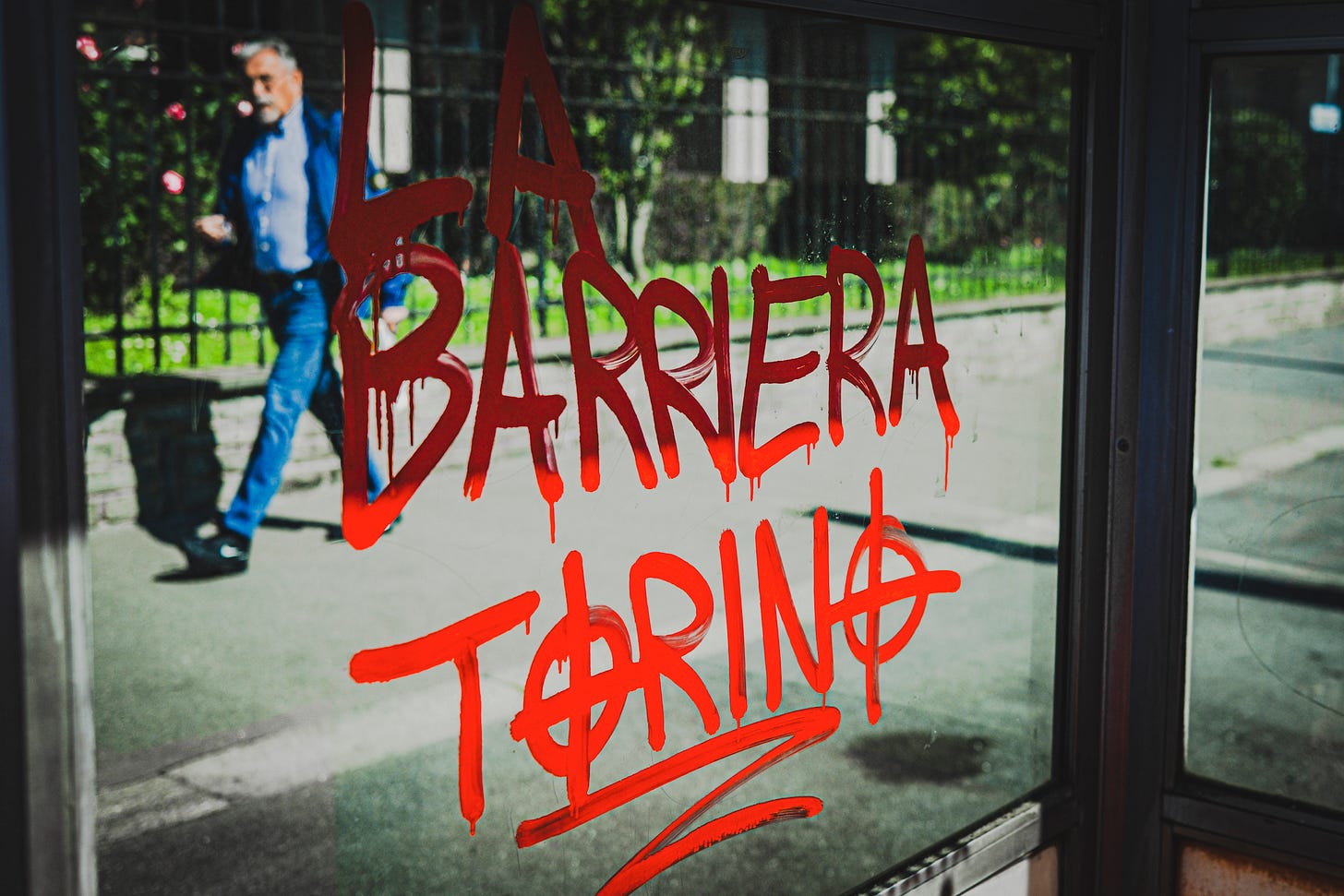

While Italy’s far-right government certainly deserves the blame, the proliferation of stickers bearing Nazi iconography and fascist graffiti takes its politics to its most feared possible conclusion.

Spread throughout the immediate neighbourhood by a local identitarian group, their boldness speaks reams about the racism being unleashed by populist electoral victories.

Like many minorities, my partner and I hope for the best possible outcome in this June’s local and EU polls. However, given what we’re witnessing, we fear for the worst.

This edition of Aperture Priorities speaks to those anxieties, with photographs of our petri dish of a neighbourhood and the rightwing forces hoping to triumph.

The final photo was shot further north, in Torino’s iconic immigrant market, Porta Palazzo.

****

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit. All rights reserved.