By Charlie Bertsch

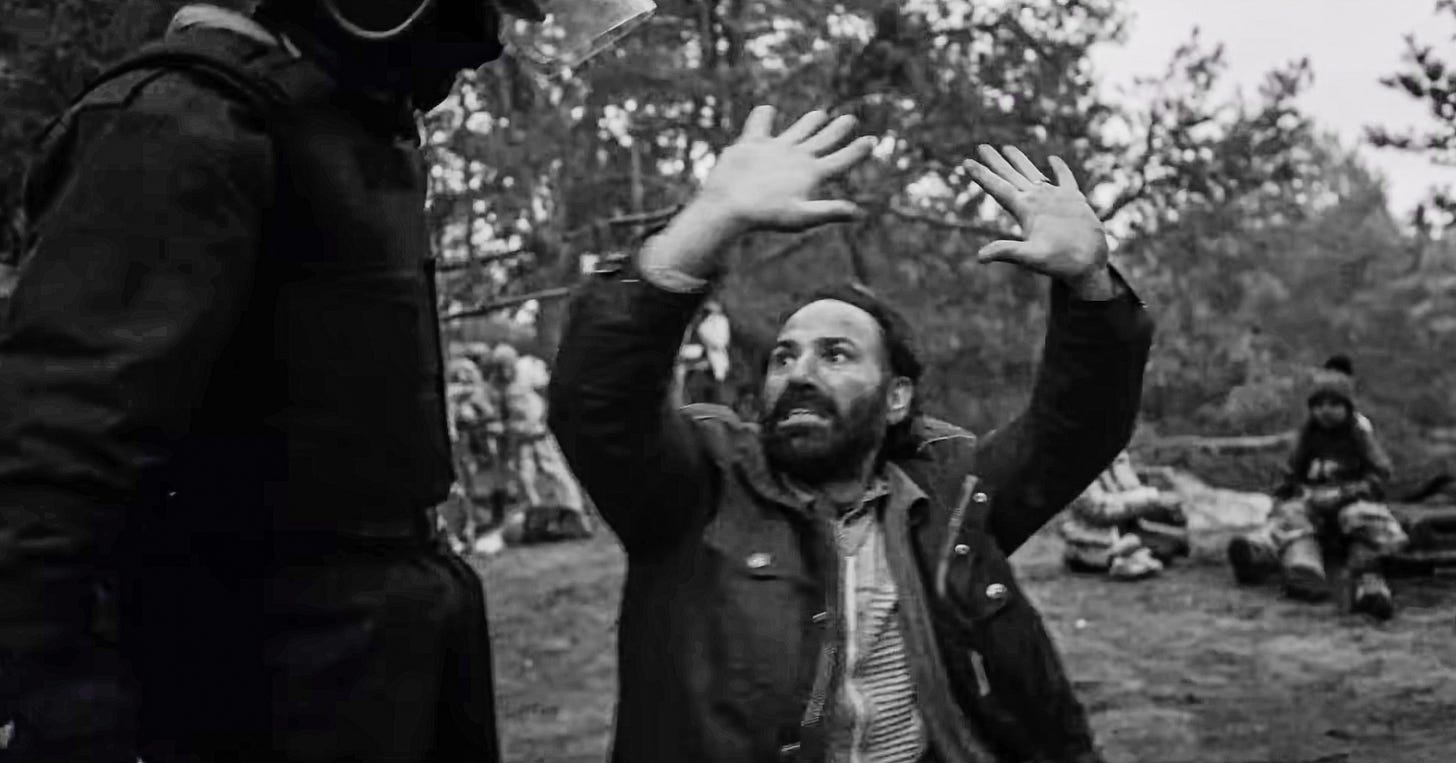

Agnieszka Holland’s latest film, Green Border, depicts the harrowing experiences of refugees who have become pawns in a new Cold War.

The term “green border” refers to the wilderness areas where nations touch, no matter the landscape’s colour.

People who cannot cross into a country the easy way, usually because of the passport they carry, try their luck in these out-of-the-way places where they have a chance of avoiding immediate capture. They often pay smugglers to help them, even though they have no guarantee that the fee is worth it.

In Holland’s film, this borderland is actually green, referring to the densely wooded territory along the border between her native Poland and Belarus, the European Union’s eastern frontier.

Significantly, however, the opening overhead shots of lush green forests fade to a black-and-white that transports us back to the high-contrast conflict of the Cold War, not to mention World War II.

Although we see a few French-speaking refugees from Africa, the film focuses on those fleeing Syria and Afghanistan.

Green Border documents a crisis manufactured by Belarussian dictator Alexandr Lukashenko, who lured desperate refugees to his country with the promise that they could easily cross the Polish border into the European Union, fully aware that they would not be welcomed there.

Lukashenko wanted to apply pressure to the Law and Justice regime in Poland, which had demonstrated an increasingly defiant attitude toward Belarus and Vladimir Putin’s Russia, for which Belarus is a proxy.

When Poles in the film regard the refugees as hapless recruits in the rapidly worsening conflict between West and East, they are repeating a reactionary political argument. But that doesn’t make it a lie.

While Green Border avoids flashy self-reflexivity, it provides an excellent framework for reflecting on a crucial topic in film theory.

Holland mobilises our structural inclination to identify with characters on screen.

It is hard not to feel for the refugees once we get to know them a little: the grandfather who refuses to let his suffering impact his faith and continues to pray regardless of the weather; the nursing mother whose milk runs dry; the boy who complains about having to wear a girl’s sweater and declares that he has seen a giraffe in the woods; the man accused of having a homosexual relationship who knows he will be killed back home even though he has a wife.

As Green Border makes brutally clear, however, the people of Holland’s native Poland are inundated with messaging designed to prevent them from perceiving the humanity in refugees from places outside of Europe.

Instead of being encouraged to care about the plight of these migrants, Poles are urged to regard them as a threat, identifying them as an impersonal problem instead of identifying with them as individuals.

After witnessing border guards treat the refugees very harshly, we watch new recruits being indoctrinated in the mindset that leads to this behaviour.

Before the Polish theatrical release of Green Border last September, leaders of the then-ruling Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) party attacked Holland for portraying her homeland so negatively.

One government minister went so far as to declare that the film was equivalent to the anti-Polish propaganda disseminated by the Third Reich.

This was ironic in light of Holland’s mixed heritage. Although her mother was Roman Catholic, her father was a Jewish communist who participated in the Polish resistance.

Reactionaries were eager to revive the Antisemitic argument that Jews promote international solidarity instead of national pride.

For anyone not hopelessly blinded by prejudice, however, it is clear that Holland’s purpose is not to defame Poland.

Rather, she wants to show how difficult it is for individuals to heed their conscience when they are repeatedly told that duty requires them to ignore it.

Although Green Border concerns a crisis at the Polish border and intends to move Polish audiences, Holland knows that the impulse to dehumanise refugees is not a problem specific to Poland.

Poland is an important front in a battle taking place throughout European society, as the surging popularity of authoritarian populist parties hostile to immigration across the continent demonstrates.

Green Border illuminates conflicts outside of Europe as well.

Listening to border guards speak disparagingly of the refugees, it is not hard to perceive a connection with the rhetoric Donald Trump and his running mate J.D. Vance have used when describing the Haitian refugees who resettled in Springfield, Ohio.

And although the United States’ border with Mexico is more brown than green, the mountainous areas of southern Arizona resemble the forests between Belarus and Poland in being too rugged to police effectively.

Not long after Green Border premiered last year, Hamas attacked Israel, triggering a retaliatory invasion that has turned the entire population of Gaza into refugees.

Now Israel is seeking to destroy Hezbollah as well as Hamas and seems poised to reduce much of southern Lebanon’s population to refugees, too.

Ethnic conflicts in Africa are also leading to the kind of border crises documented in Holland’s film.

Green Border underscores the role of technology in our lives. So long as the refugees are able to use their mobile devices, they are confident that things will work out. But once their batteries run down or, worse still, the devices are damaged by the elements or the malice of border guards, the asylum seekers begin to comprehend the degree to which they have become pariahs.

At one point, after a group of activists locates the refugees and begins ministering to their needs, we cut to a series of stationary camera shots meant to simulate a camcorder’s view. One refugee after another looks directly into the camera and tells their story.

These testimonials represent the kind of direct appeal used to solicit donations for refugee organisations. The presence of technology both rehumanises the refugees and instrumentalises their suffering.

In order for the suffering to be felt by people who might be willing to help, it has to be properly framed.

Holland is too supple a filmmaker to turn Green Border into a heavy-handed allegory. Its characters are too specific to be mere stereotypes.

Nevertheless, the film invites audiences to treat it as a funhouse mirror, exaggerating their best and worst tendencies.

The activists who try to help the refugees along Poland’s border with Belarus show us what a humane response to the suffering of migrants should look like.

The border guards who cruelly abuse them demonstrate the opposite, showing how dehumanisation works.

At times, Green Border feels like Spike Lee’s 1989 film Do the Right Thing, which revealed a range of possible reactions to a crisis and invited us to make a choice.

Although Holland’s film is relentlessly depressing, the fact that it not only made it into production but ended up being a minor box-office success in Poland offers a glimmer of hope.

Green Border shows that there is still a market for serious films that do not pander but instead present us with the harsh truths of a world where common decency is an endangered species.

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

Screenshot courtesy of KinoSwiatPL/Wikimedia. Published under a Creative Commons license.