More Journalism, Less Data

Aperture Priorities Contact Sheet #18

By Joel Schalit

Journalists underrate time. Trained to produce scoops, our internal clocks look forward, not back.

In agency and government reporting, the urgency of the present often closes our eyes to the significance of context.

Historical framing is always limited, at best, to the immediate past.

EU and American coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian war in Gaza is a case in point. Very little, if any, has contextualised it in light of previous Israeli campaigns in the territory.

The 1982 Lebanon war is essential for understanding the conflict. From the body count - estimated at 48K - to the IDF’s destruction of West Beirut, there’s a lot of repetition in the making.

It's high time we shift our focus to the bigger picture, to the historical underpinnings that shape the present, to understand how events like the Gaza war are simply more of the same.

They might be initiated by different circumstances and appear more brutal because of the prominence of citizen journalism and soldiers’ social media posts, but the wars are eerily similar.

You shouldn’t have to be an academic to recognise such things. This responsibility is also a journalistic one, and it is readily researchable.

It’s not just a foreign problem. Middle Eastern reporting is often hobbled by similar limitations in covering the Gaza war and other crises.

Speaking as an Israeli journalist, Israeli media have to deal with far more institutional constraints than their American and European counterparts.

You can see the difference in headlines in Israeli and foreign papers, where a newspaper like the New York Times will run feature exposés on the Gaza war that barely get airtime in Israel.

That doesn’t excuse foreign newspapers like the NYT from responsibility. Its reporting on the Gaza conflict has been inconsistent and attacked for being biased.

The newspaper’s good coverage has been an exception to the rule of an otherwise typically problematic foreign platform that won’t go deeper.

The same holds for how many European media have covered the build-up to an anticipated far-right victory in this week’s EU elections.

We’ve known the results for months, based on the repetitive speculation and opinion polling, whose survey questions and interviewees we assume are trustworthy.

Looking at the exit polls for the Dutch vote when this article was written, in which the GroenLinks-Labour bloc leads with eight seats, I’m relieved at the results and upset at how much I was primed for something else.

It wasn’t supposed to happen. Geert Wilders’ PVV party has been consistently predicted to win, as though, due to his far-right politics, he was a harbinger of a new order.

Yet, he only won 23.5% of the vote in last November’s national election. While Wilders secured the biggest percentage, that’s still only a quarter of the electorate. It wasn’t a full sweep.

Undoubtedly, Dutch politics is not an expert beat for most foreign news media. Appreciating the nuances of the country’s politics and historic liberalism is not a standard competency.

The six months it took Geert Wilders to form a government took their toll, as have the protests against the Gaza war in the Netherlands, which reinvigorated cultural and political divides.

That doesn’t mean Wilders didn’t do well. Exit polls have his PVV party in second place. But it’s far from the change in worldview ascribed to his previous victory and other far-right wins.

As an editor, I would have liked to read more complex coverage of national politics in EU member states like the Netherlands that more accurately reflects their mood.

Especially given the Netherlands' historically liberal consensus, which made the rise of populist politics in the country, starting with the late Pim Fortuyn, who was assassinated in 2002 by an environmental and animal rights activist, a big shock.

Not to mention the role of Russian disinformation efforts in the country during the 2016 referendum on Ukraine’s association agreement with the EU, which was rejected. It was the first sign of Kremlin interference in a Union vote.

Chalk it up to an overreliance on polls and statistics, which are used in place of investigative journalism and local reporting. Media may have to spend more, but the journalism is better.

Indeed, revisiting history like this, in interviews with Dutch voters or discussing the war in Gaza with minority voters, particularly of Muslim background, would have yielded a different picture.

Geert Wilders is an avowed Philosemite and was an early advocate of far-right support for Israel as a Western outpost in the Middle East.

It’s not inconceivable that this has become a problem for the PVV and will prove a bigger problem for Wilders and his government moving forward.

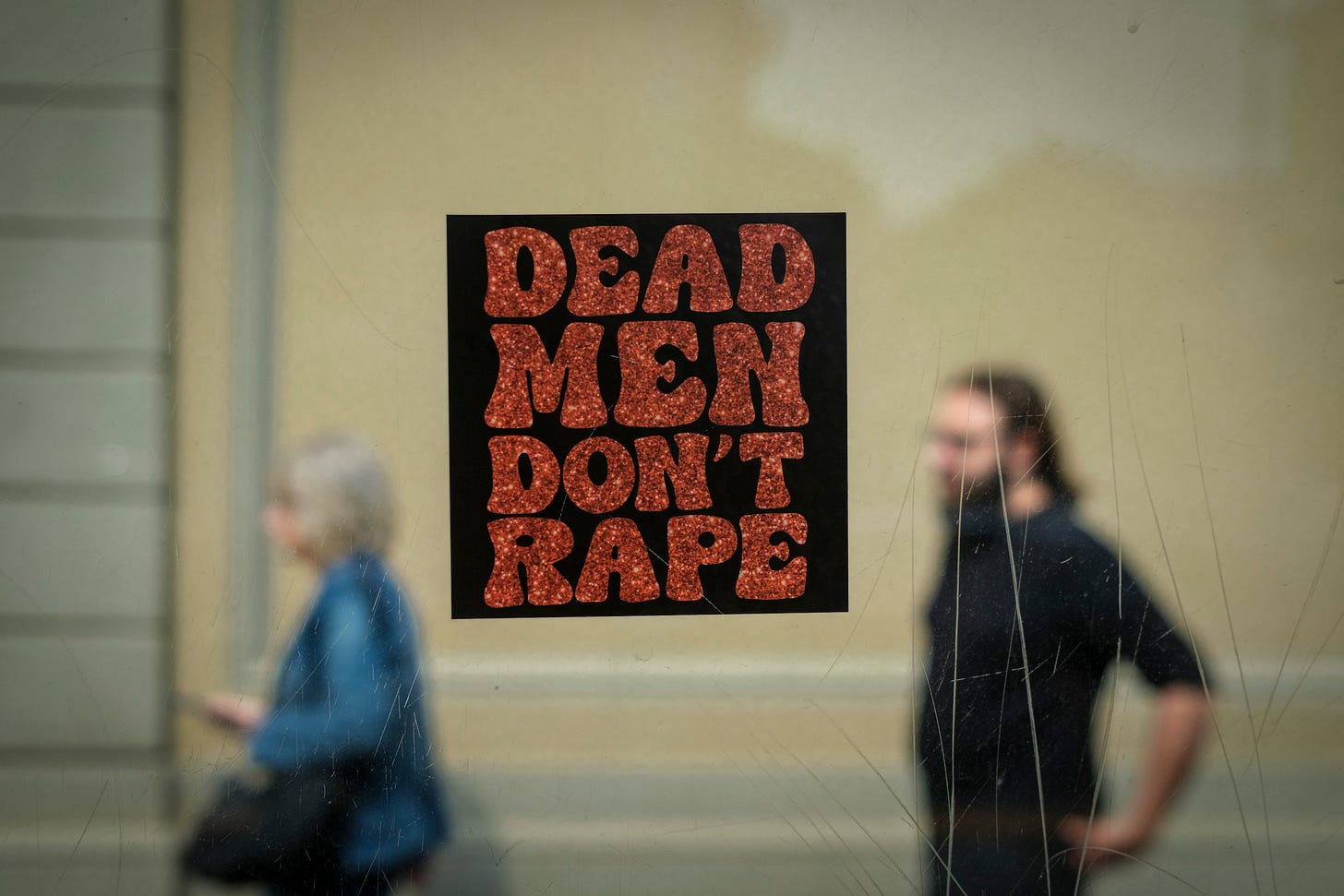

Hence, this week’s Aperture Priorities selection starts with the EU elections and works its way back to protests against Israel’s Gaza campaign in Italy.

****

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

Photographs courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.