Protest in Code

Natalie Beridze’s Street Life

By Charlie Bertsch

Natalie Beridze’s stunning new album Street Life transforms field recordings of recent protests in her native Georgia into deeply compelling ambient music.

For most people, political music is still defined by protest songs, from the consciousness-raising folk of Bob Dylan to the punk of The Clash to the hip-hop of Public Enemy, the sort that stirs up rebellious feelings.

Street Life sounds nothing like that.

This music only makes a political statement because the liner notes make a political statement about the music.

Although Beridze explains that the raw material for the record derives from protests that followed the populist and Vladimir Putin-friendly Georgian Dream party’ disputed electoral triumph last October, it’s hard for listeners to discern anything concrete.

Even compared with the spare, involuted compositions for which the prolific Beridze is known, Street Life is austere.

The opener, “Minute Portion of Matter”, features a keening, insistent whistle and what sounds like reverb-drenched voices that have devolved into a pre-linguistic cacophony.

On “Cadence”, the voices return, sounding somewhat more human, yet all the more disturbing as a consequence, as if we were listening to the soundtrack of a horror film about the black arts.

“Symbol inside”, the record’s final number, is the only one for which Beridze permitted herself to supplement the field recordings with sounds from instruments. But their billowing sine waves don’t feel like a significant departure from the previous tracks.

Street Life works beautifully on an abstract level, particularly with good speakers or headphones. As the volume swells, there is a sense that sounds from the left and right channels are converging in the centre before then separating as they grow quieter.

Once we know where the music comes from, however, pure listening gives way to a listening for, as we try to figure out what Beridze is trying to communicate about the political situation in her homeland.

Natalie Beridze’s musical career so far has been bookended by two protest movements, the Rose Revolution of 2003 that overthrew former Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze’s dictatorial government and the current one.

The Rose Revolution was celebrated for its non-violent character as protesters marched into the Georgian parliament carrying red roses.

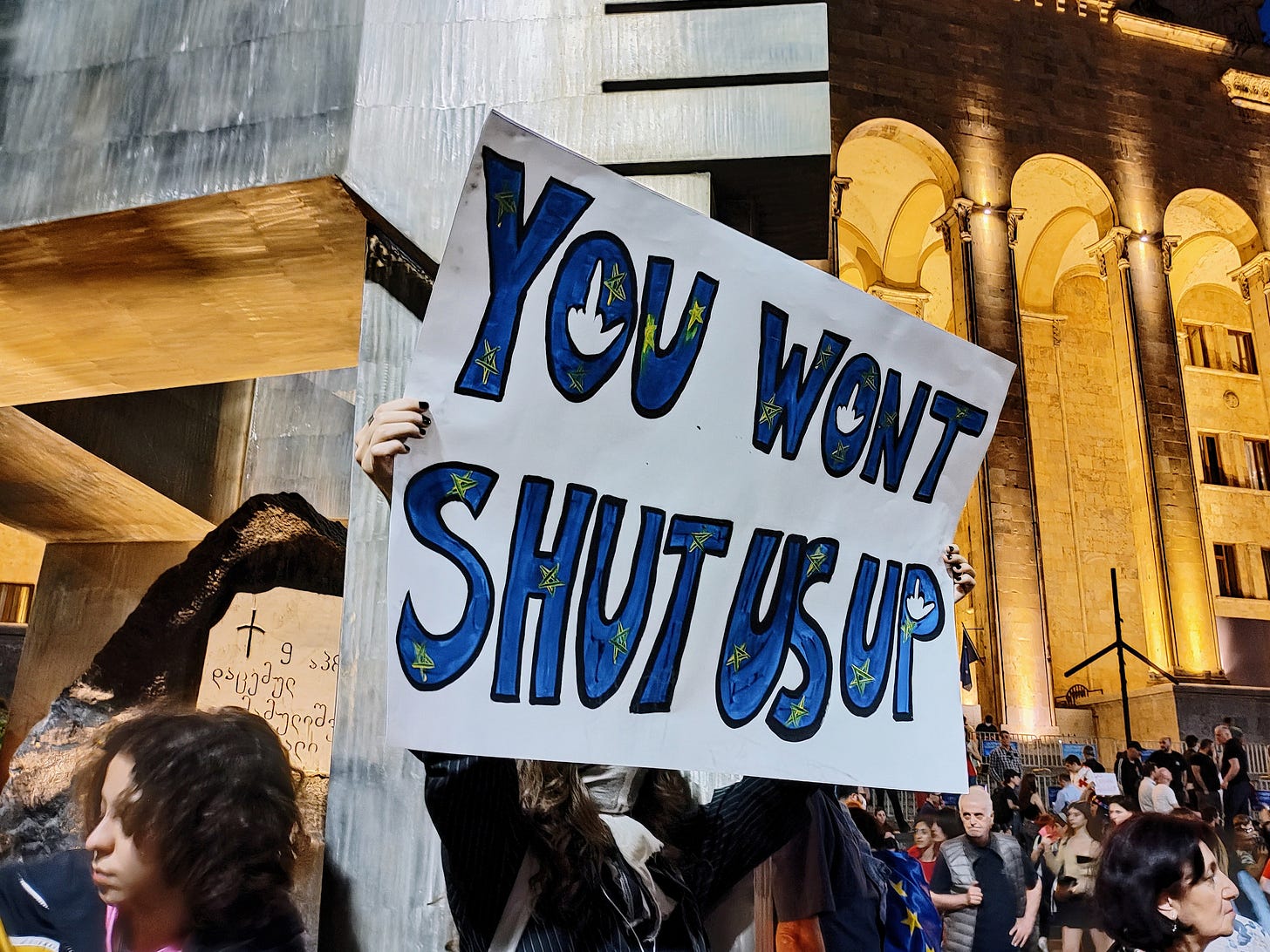

During the protests that have been taking place since October’s disputed election, by contrast, the government response has been much harsher.

After a new wave started up in January, imprisoned journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli began a hunger strike. Former Tbilisi mayor Gigi Ugulava and opposition leader Nika Melia have also been arrested.

Given Georgia’s precarious location in the Caucasus region, bordering the parts of Russia most resistant to Moscow, the fact that it is now governed by politicians eager to do Putin’s bidding is deeply concerning for those residents who support democratic values.

Because the protests against Georgian Dream started as a grassroots phenomenon, it has proven difficult to extinguish, even though its ostensible leaders have been arrested.

Perhaps Beridze decided to foreground the abstract quality of the field recordings for this reason.

What we get is not the sense of a political vanguard but overlapping flows of energy that are hard to channel in pursuing a particular goal.

This approach is complemented by the way individual voices dissolve into a crowd. This quality can be interpreted as both a strength and a weakness. Many-headed movements can’t be stopped by removing their leaders, but they also tend to be less efficient.

Street Life also communicates nostalgia for better times, particularly the Rose Revolution and its immediate aftermath.

That might explain why the tracks sometimes call early Burial records to mind.

If Burial sounded, in Mark Fisher’s famous description, like London “after the rave”, a place where heterotopian impulses only persist through haunting, then Street Life conveys a sense that the ghosts of Georgia’s past might be impeding its hopes for the future.

Burial isn’t the only musician from the early 2000s that can be discerned in Beridze’s compositions. The use of found sounds as building blocks hearkens back to the pioneering efforts of Matthew Herbert and Matmos.

But the record that Street Life reminds me of more than any other is Montreal duo [The User]’s 2003 album Abandon.

Although the artist is better known for two “symphonies” comprised of sounds from dot matrix printers, Abandon is more aesthetically compelling, capturing the way sounds are shaped within empty grain silos. The result is a haunted soundscape, as beautiful as it is eerie.

What sets Street Life apart is that Beridze must contend with recordings that are not only saturated with meaning but potentially dangerous for those who appear in them. The music’s abstraction might also reflect a concern with making participants identifiable. No one is going to get arrested because of the album.

Because the Georgian language is extremely difficult for people in the West to learn, recordings in which the chanting of slogans was intelligible would have made Street Life more alienating for international audiences.

Instead, we are permitted to identify with the protesters collectively without being able to identify them as individuals.

At a time when technological surveillance has never been easier or more exhaustive, producing works of art like Street Life may turn out to be the best way of making a political impact.

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

Photograph courtesy of Jeiger Groeneveld. Published under a Creative Commons license.