By Henrietta Foster

Buried in Rottingdean, Angela Thirkell wrote a book about the three houses she remembered from childhood.

First is the beautiful Georgian mansion, The Grange, where her grandfather, the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, lived. It is now a rather undistinguished 1960s housing estate at the top of the North End Road in West Kensington.

Second is her family home next to a public house in Young Street off Kensington High Street. The pub still exists, but that house has also been pulled down and is now a grim, tangerine 1990s office building.

Finally, her grandfather’s country house in Rottingdean still exists, including the special slip built in the facade to transport his canvases from his upstairs studio.

Three Houses is a wonderful and forgotten book about a bygone age, and it has moved me to write this article about three women who have exhibitions about their work and the three houses that inspired them.

Rottingdean is a far-flung outer borough of Brighton in East Sussex. It is a strange but uplifting experience to leave the main drag of an increasingly more and more urban Brighton for the idyll that is Rottingdean.

You can take a bus from outside the elegant railway station or walk a bracing four miles along the seafront to get there. A village green, a duckpond, two churches, and gorgeous Georgian houses await you.

Such notables as Edward Burne-Jones, Rudyard Kipling, Alfred Noyes, William Nicholson and Enid Bagnold were former residents.

On the horizon is the famous windmill that was supposedly the inspiration for the symbol of the Heinemann Press. That symbol was based on a woodcut by Nicholson, who lived in the village from 1909 to 1914.

Nicholson first went to Rottingdean in 1897 to make sketches for a portrait of Kipling, who was staying with his uncle Edward Burne-Jones. Nicholson took his family with him for a brief holiday away from smoky London.

They all fell in love with the place, ideally located between rolling hills and the sparkling seaside. Even now, despite the nearby grim postwar bungalows and the many fish and chip shops, there is no finer place to be on a brilliant summer day. It is the kind of place that most true Brits dream of retiring to.

In 1909, Nicholson bought the former vicarage, which he renamed The Grange. Built in 1740, it is a handsome creamy vanilla stucco villa with solid columns and wrought iron balconies galore—the perfect country house within the context of the perfect country village.

Eventually, Nicholson got Edwin Lutyens to redesign the interior and Gertrude Jekyll to plan out a large country garden in which a dark clapboard studio was built for him and his wife.

Sadly, visiting Canadian airmen during the Second World War destroyed the house’s Lutyens interior. The garden has been sold off so that nothing of Jekyll’s design remains, and the wooden studio is now on the grounds of a nearby school.

The Grange is the public library and has seen better days. How wonderful it still must be to sit in this beautiful house on a cold winter day and read books or perhaps visit its tremendous cafe, where a perfect cream tea or divine knickerbocker glory can be consumed in that cliché of all clichés: an English country garden.

Paul Nash visited the family at The Grange and said that it was indeed the perfect country house full of stiff chintzes of gay pinks and greys and highly polished wood. People loved the house, and it was there in their joint studio that William Nicholson and his wife, Mabel Pryde Nicholson, produced their best work.

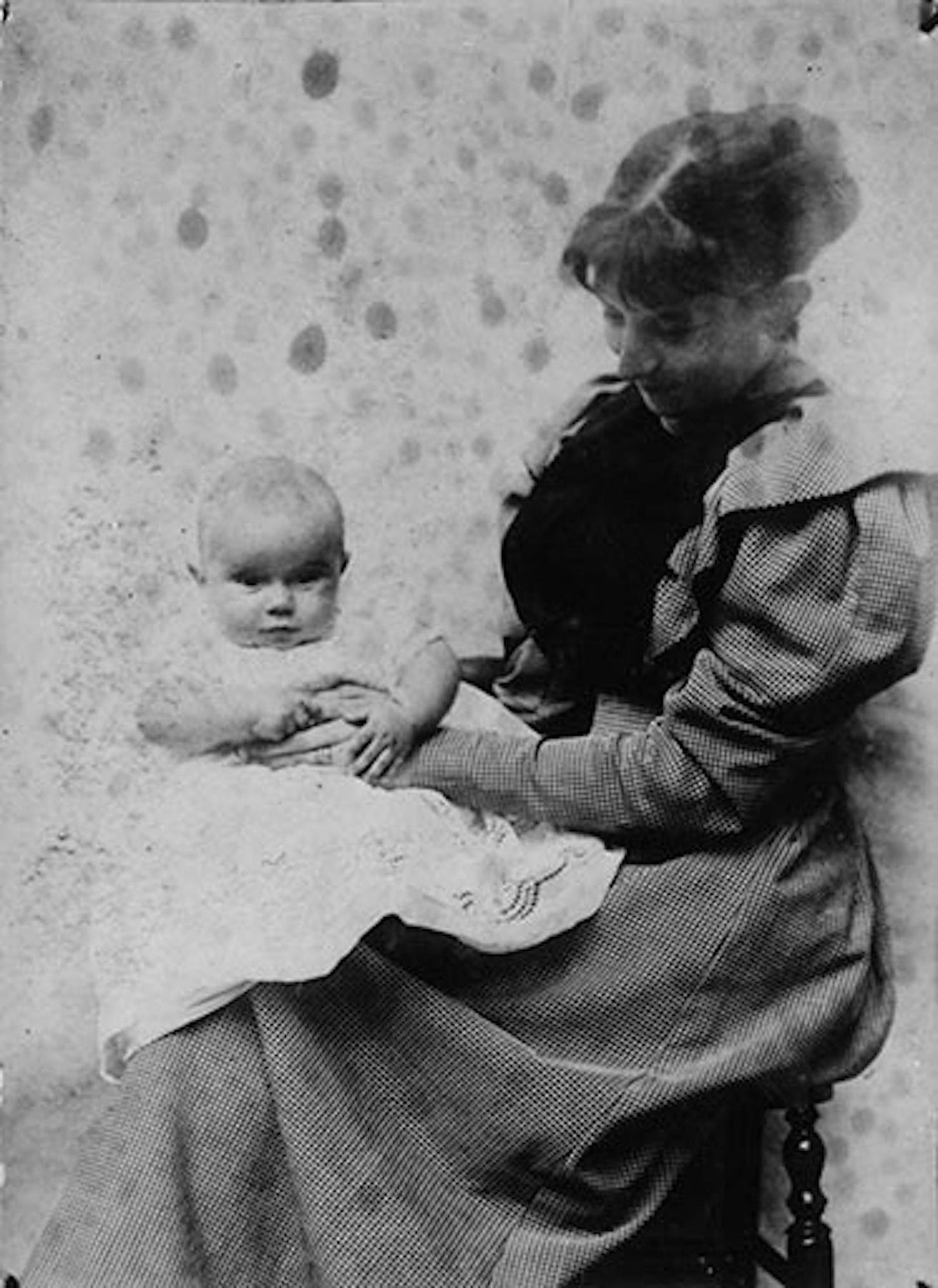

On the first floor of this somewhat scruffy public library is a truly exceptional exhibition devoted to the work of Mabel Pryde Nicholson. Prydie: The Life and Art of Mabel Pryde Nicholson is the first exhibition of her work since the one organised by her son Ben Nicholson a couple of years after she died in London in 1920.

Mabel Pryde Nicholson has been forgotten—a lost artist who is no more than a footnote in art history. Wife of the prolific Edwardian artist William Nicholson, she was the mother of the much-admired Ben Nicholson, the architect Christopher Nicholson, and the painter Nancy Nicholson, who was married to Robert Graves of I Claudius fame.

She was a woman defined by the people she was related to rather than the work she herself did. Her own work has been languishing in private collections for over 100 years. One was found for this present exhibition just days before it opened..

Born Mabel Pryde in 1871, she was the daughter of the headmaster of Edinburgh Ladies’ College. Her brother, James Pryde, was also a well-known artist.

She went to the Bushey School of Art in Hertfordshire, where she met William Nicholson, whom she married in 1893 unbeknownst to their respective families. Nicholson and her brother worked together in the 1890s as graphic artists known as J. & W. Beggarstaff.

In his time, Nicholson achieved notoriety as a portraitist and not for the luminous still lives which we now know him for today. He was an inconstant husband, leading his son Ben to describe Pryde as ‘ the rock on which my whole existence has been based.’

Mabel Pryde Nicholson was a wife and mother during the beginning of the suffragette movement. In her lifetime, she had works in group exhibitions and a solo show in 1912.

However, raising her four children became the mainstay of Pryde Nicholson’s existence until they moved into The Grange, where she could devote more time to her paintings.

Dark shadowy paintings of all her children in dressing up clothes or lolling about on those stiff chintzes exemplify a vital talent that has been neglected. Even if just for her portraits of them, Pryde Nicholson should have been remembered. But there is so much more.

Mabel Pryde Nicholson died at the age of 47 from the Spanish influenza epidemic and just a few months before the death of her soldier son Anthony in 1918. This splendid exhibition at the Grange ensures she will no longer be forgotten.

Our second house is still a private residence and sadly impossible to visit. But its spirit hovers over another tremendous exhibition at the Petersfield Museum and Art Gallery just over the border from Sussex in nearby Hampshire.

The house in question is Yew Tree Cottage in the village of Hurst on the Hampshire Sussex borders, and the woman in question is the art collector Peggy Guggenheim, who lived in this sleepy corner of the home counties from 1934 to 1939.

Guggenheim is better known for her eponymous museum in Venice, her fabulous art collection, and her extremely torrid love life.

Peggy Guggenheim: Petersfield to Palazzo focuses on what turned her from a perennially dissatisfied wife and mother into a world-class art collector and gallerist. The curators believe that the transformation took place right there in their own backyard and was in part due to that tumultuous private life.

Peggy Guggenheim arrived in Hampshire in 1934 after her most recent lover and companion, John Helms, died on the operating of all things table from a broken wrist.

Her children, Pegeen and Sindbad, from her first marriage to Laurence Vail, were with her, and so was her new lover, Douglas Garman. Sindbad’s daughter Karole Vail co-curated the exhibition with Louise Weller. Vail is also the director of her grandmother’s palazzo museum in Venice.

The lovers chose this part of the county because Garman’s mother lived nearby with his children from a previous marriage. After renting Warblington Castle for the summer, Guggenheim bought the secluded Elizabethan cottage and settled into rural life.

Pegeen went to the village school, Sindbad became obsessed with cricket at the local matches, and they all attended their cook’s wedding to their gardener.

There is a report of a speeding ticket that Guggenheim received and a card from a jewellery shop where she might have sold her mother’s silver tea service. For those five years, she tried to settle into domestic life, albeit with regular trips up to London.

Garman had promised to marry her if Edward VIII married Mrs Simpson, but he failed to deliver on that promise after his abdication speech.

In the end, the relationship became violent. Garman soon left her first for the civil war in Spain and then for a British working-class woman who was as devoted to socialism as he was.

Guggenheim was once more on her own, but not for long. She claimed to have slept with over a thousand lovers in her lifetime. Many of them have become household names, and many have visited Petersfield.

Once Garman decided he loved communism more than her, she invited a whole panoply of lovers to spend the weekend in her Alexander Calder bed. In many ways, it was a sad and lonely life. Perhaps it took the isolation of an English country village for Guggenheim to realise that she needed so much more.

Her good friend Peggy Waldman wrote in May 1937, “I wish you would do some serious work.” “You’d be so much better off than waiting around for G. to come weekends and tear you to bits.”

Those suggestions included setting up a publishing company or starting her own art gallery. She chose the latter, and Guggenheim Jeune was launched in 1938 on Cork Street, London.

The show includes a photograph of Guggenheim and the renowned British art critic Herbert Read. In her hand is a list of artists they felt were necessary for her plan to create a museum of the future. The photo remains, but the tantalising list has been lost.

Many a column inch has been spent deciding who should be on that list. This beautifully researched show gives us an idea, with works by Henry Moore, Max Ernst, Vassily Kandinsky, Jean Cocteau, Rita Kernn-Larsen, Roland Penrose, John Tunnard, Julian Trevelyan, and many more.

Guggenheim declared at the end of her life and from her Venetian palazzo, “I dedicated myself to my collection .. it was what I wanted to do, and I made it my life’s work. I am not an art collector. I am a museum.”

It is a grandiose claim, but this exhibition helps us understand why and how she made it. Guggenheim was never an easy person and had a tragic private life.

Her father was lost on the Titanic, her beloved elder sister died in childbirth, and her other sister’s infant children fell to their deaths off the balcony of a friend’s Manhattan apartment.

The least beautiful of three sisters, she was trapped in her own restlessness and feelings of inadequacy. Perhaps the one happy and settled time in her life was at Yew Tree Cottage. She said it was “very good for me to be a simple woman and do normal domestic things for a change”.

The third house is more of a memory than a reality but permeates Leonora Carrington’s work. It never appears in our final summer show other than by suggestion. It is Crookhey Hall – her childhood home in Lancashire.

Built in 1874 by the architect Alfred Waterhouse in what has come to be called the grimly Gothic style, it is now a school. The house never left Carrington’s psyche. In a BBC interview from her final home in Mexico City, she said, “I always had access to other worlds – we all do when we sleep and dream.”

Those dreams were of Crookhey Hall, which appears throughout her work. There, she plays a lonely little girl shunned by her three brothers and loathed by her French governess.

Crookhey Hall was again and again her blank canvas, appearing throughout her painted and written works.

In the same interview, she asked, “Do you think anyone ever escapes their childhood? I don’t think we do, or that feeling you have in childhood of things being mysterious.”

The dark, rather imposing house was a launchpad into high society for Carrington’s upwardly mobile family, who became immensely nouveau riche thanks to their textile factories. Hunting, balls and the social whirl were all possible.

Who Carrington married was vital for the family and its future social position. She was a debutante and presented to the king at court in a white silk frock with a diamond tiara.

In 1939, she wrote a terrifying fictional account about it called The Debutante, in which the young woman in question is befriended by a hyena at the Zoological Gardens who offers to replace her at court.

For Carrington, the social season was torture, and rather than be “sold to the highest bidder”, she escaped to art school where she encountered surrealism thanks to a gift from her mother of Herbert Read’s book on the subject.

This is not the only overlap between Carrington and Guggenheim. Both were from very wealthy but self-made families. Both were restless and frustrated by the path their parents expected them to tread. And both were outsiders. Carrington was the Roman Catholic daughter of a nouveau-riche family, and Guggenheim was the granddaughter of a self-made Jewish copper baron.

Both wanted more from life and were fascinated by art, and la vie boheme. However, Carrington was a great beauty and became a great artist. Guggenheim knew that no one could call her a beauty, and her talent was for collecting men and art, not creating.

In Read’s book, Carrington was captivated by a painting by the German artist Max Ernst, Two Children Frightened by a Nightingale. In 1936, both women attended the London International Surrealist Exhibition and saw Ernst’s paintings in person for the first time. It was a coup de foudre for both of them.

In 1937, Carrington met Max Ernst at a supper party in London and quickly became his lover. They both returned to Paris and began to live together.

Before leaving for France, she went to Crookhey Hall to tell her father that she would live with a penniless artist who was already married rather than a duke’s son or a minor royal. She never saw her father nor, indeed, Crookhey Hall again.

The exhibition is curated by her cousin Joanna Moorhead, who starts it with beautiful photographs of Carrington’s new life by her friend Lee Miller.

Taken in Cornwall and then at their home in the south of France, we see Carrington with Max Ernst and their friends Paul Eluard, Man Ray, Eileen Agar, Henry Moore, and Roland Penrose. Half-clothed and enjoying their freedom in glorious sunshine, they present quite an alternative to the gloomy Lancastrian citadel she had just escaped.

Max Ernst was Carrington’s first companion and Peggy Guggenheim’s second husband. At the outbreak of war, he was interned twice as a hostile alien. In desperation, she sold their house for a bottle of brandy and escaped into nearby Spain.

Carrington had a severe nervous breakdown and was committed by her parents to an asylum. She noted later on that her parents cared about her enough to send her elderly nanny to Spain to look after her but not enough to come themselves.

She escaped to Portugal when she realised they would send her to South Africa. She was not going to spend the rest of her life in a remote mental hospital be like Camille Claudel. She also went to New York, where she saw Ernst most days despite his marriage to Guggenheim.

Ernst never stopped longing for Carrington’s luminous beauty and wit, even if Guggenheim’s money saved him from certain death in war-torn Europe. In the end, he abandoned both of them for the American painter Dorothea Tanning.

Carrington ended up in Mexico City, where she became the wife of a Hungarian Jewish photographer, with whom she was very happy and who had two sons.

Leonora Carrington: Rebel Visionary in Petworth only has one actual painting by Carrington and too many lithographs for sale. There are her far less interesting sculptures and her very elaborate masks.

The audiovisual accompaniments are the best: an interview she gave in the 1970s with an American filmmaker about feminism and then a hastily filmed interview with her cousin Joanna Moorhead, who was then new to the world of art.

Moorehead tells Carrington somewhat nervously how much she likes Diego Rivera’s work, only to receive withering contempt. Carrington is keen to make a difference between writing or thinking about art and doing it.

In resonant, clipped 1930s English, she says,” Doing it is the point, not talking about it.” When asked where she got her talent, she says, “My mother used to paint biscuit boxes for jumble sales.” Sadly, none of them still exist.

The three houses are rather imposing and grand. Despite their similarities, the three women are very different, except they all had a certain shyness or insecurity.

Mabel Pryde Nicholson hid behind her philandering dandy of a husband and looked after her four children. She only rekindled her desire to paint once her children were old enough to care of themselves.

She only had a few years left, but her work is up there with Whistler, Singer Sargent, and William Nicholson himself. Carrington was drowning in money and self-pity.

After a ragged and listless private life, she became an important collector.

Unfortunately, Carrington never managed any equilibrium in her private life. She retired on the Grand Canal, wearing exotic custom-made sunglasses, surrounded by many yapping Lhasa Apsos terriers.

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

Yew Tree Cottage photograph courtesy of the Emily Holmes Coleman Estate. All rights reserved. Mabel Pryde Nicholson portrait courtesy of Milton Sonn. Published under a Creative Commons license.