When Governance Falters

A Greek Tragedy: One Day, a Deadly Shipwreck, and the Human Cost of the Refugee Crisis, by Jeanne Carstensen

By Gary Isaac Wolf

Tag. Kick the can. Red light, green light. These are the backyard games I played as a child in the United States. Certainly, they have equivalents and variations worldwide.

One player is the authority, the hunter, the guard, the threat. The rest attempt to roam free, escape, get to home base, and cross a finish line. They are just games because there are rules, a goal, and the reassuring knowledge that losing is harmless.

The many variations in the routes smugglers used to take refugees from Turkey to Greece during the surge in immigration ten years ago were also called games. But this was slang rooted in cynicism, as the consequences of losing were fatal.

A Greek Tragedy, by Jeanne Carstensen, tells the story of passengers on a ship that left the Turkish coast during the fall of 2015, a time when over 1 million people were fleeing war and persecution in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Lebanon.

The ship boarded over three hundred people from Sivrice, a coastal settlement with a few guesthouses, small hotels, and restaurants. Passengers included an Afghan bank manager named Hedayat Habibyar, his pregnant wife Zohra and their two young children, Usman and Abukar; Okba Bader, a Syrian psychologist and school counsellor; Kabul-based TV journalist Naseer Sekandari, his wife Fatima and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Rezwana; and Amel Alzakout, a Syrian artist and filmmaker.

Sivrice is on the south side of the Biga Peninsula, which extends into the Aegean Sea, and from the shore the northern coast of Lesvos is clearly visible across the Mytilini Strait, just a few miles away. Barely a quarter hour after motoring into open water, the ship broke apart.

An exact count of the people who perished has never been possible since there was no passenger manifest, and not all bodies were recovered. Perhaps seventy people died, including many children. Hedayat Habibyar lost his entire family; Rezwana was orphaned; Okba Bader and Amel Alzakout survived after desperate rescues.

The scenes that afternoon were harrowing, clearly visible both in person from the Greek shore and remotely on the internet and in the news. The cruelty of the smugglers’ business model that sent them to destruction and the legal and bureaucratic system that led to improvised and chaotic rescue efforts, with families drowning just minutes by boat from the shore, shocked the world‘s conscience.

But I must take that back. “Shocked the world’s conscience” is a myth and one of many that Carstensen refuses to honour. The people who were shocked were spread around the world, but they were not very numerous or very powerful, and it wasn’t long before attention moved on.

Carstensen is not the first to trace these events and try to bring their vague horror, punctuated by vivid but fragmentary images in the press, into a coherent and factual narrative. The artist Amel Alzakout wore a waterproof wrist camera when she boarded the ship. Her intention was to document her journey to Europe.

After the wreck, Alzakout collaborated with the investigative team Forensic Architecture, which specialises in the reconstruction of events associated with state violence and human rights abuses, to do a moment-by-moment timeline, film, and exhibition: Shipwreck at the Threshold of Europe, Lesvos, Aegean Sea.

While crediting this investigation in her book, Jeanne Carstensen’s purpose is different. Forensic Architecture builds a narrative basis for accountability. Carstensen explores the deep personal connection between traveller and host, refugee and rescuer. Her portraits of the asylum seekers and the people who came to their aid—international volunteers, local restaurant workers, Greek and Turkish fishermen, and lifeguards from Catalonia—are vivid and dramatic.

But I allowed myself to ask: what purpose does Carstensen’s method serve? In the face of organised violence and betrayal, is it right to hold us so long in narrative, in individuality, in personal experience? We’re compelled, truly, but this can’t be reason enough.

Carstensen anticipates this question in her preface and writes that tragic dramas warn of impending disaster. She recreates these encounters to prevent the shipwrecked passenger struggling in the Aegean or the traumatised teenager searching for her parents in the hours after the wreck from being abstracted into mere incidents, increments in a body count.

Through making us feel something of what happened, emotionally, on both sides of the experience, A Greek Tragedy gives a foretaste of our own desperation when governance fails and we’re plunged into the terror of the wreck or the improvisation on shore.

There aren’t many background facts here, perhaps because the author understands that “learning about displacement” won’t stop it. It is very easy to know these facts. We may have made treacherous journeys ourselves, or our parents or grandparents did.

Many of the inhabitants of Lesvos are descendants of Christians fleeing Turkey a century earlier, and we can hop back through the centuries without finding a single one uncontaminated by forced emigration. Children of refugee families fleeing the infamous massacre of the Latins in Constantinople probably drowned in this same Aegean— and that only takes us back as far as 1182.

—

Stratis Valamios, a fisherman and part-time cook at one of the seaside restaurants on Lesvos, spent the morning of 28 October running a hair dryer across the body of a child suffering from extreme hypothermia after an earlier smuggler’s boat with dozens of refugees capsized off the coast.

He was just back at work at the restaurant, cooking for a group of tourists, when news of the larger disaster came in. Valamios went directly to his twelve-foot fishing boat in his jeans and t-shirt and spent the next hours pulling people from the water.

The fisherman angrily rejects the word heroism to describe his efforts of that week because it implies that compassion is unusual and unexpected. “If you want to be called human and not a dog or a cat, you have to help,” he said.

Carstensen uses the word instinct many times to describe the actions of the people of Lesvos. Here is a typical passage about two people involved in the rescue: Adamantia Skourdi, a nursing student, and her husband, Theodoros Nousias, a doctor and the island’s only coroner:

Every moment he had a break, Nousias rushed back to the hospital to assist the other doctors and to check in on his wife, Adamantia, and the little boy who so resembled their son. Against all odds, the child, who was in a state of profound hypothermia, had survived the night. Adamantia had stayed with him, pressing his frozen body against hers underneath the blankets, skin to skin. She was a nursing student, but her form of care didn’t have anything to do with her medical training. It was gut, maternal instinct. Keep the child close, as you would a newborn.

Olga Iordanou, a pediatric nurse, was at the main hospital in Mytilene that night, where most of the severely injured children were transferred. Iordanou was joined by other women volunteers. Their instructions were simple: “Sit with them, change them, change their diapers, caress them, become their mother.”

As Carstensen’s close look at that terrible day continues, she makes us want to believe that Stratis Valamios is right. Self-respect bars us from accepting that it’s out of the ordinary to comfort a dying child, wrap a shivering teenager in a blanket, or motor out a few miles in your reliable fishing boat to give drowning people a hand out of the water.

Why, then, did the appointed authorities find it so hard? Could it be that not everybody is equally capable of pity, or even that we might be unable to notice our own instincts of care and yield to them when we are needed?

Many things can hold us back. Refugees had been crowding the beaches and small streets of the Greek island all summer, interfering with business by the mere fact of their suffering. Although Carstensen doesn’t give voice to the anti-immigrant faction or sympathise with their hostility, she does acknowledge that the context of the disaster included local as well as national and international antipathy to people without money to spend, with nowhere to rest except in public, carrying the stigma of trauma.

Austerity measures imposed on Greece after the financial crisis had hurt confidence and damaged public institutions, and Carstensen hints at a background of passivity and resentment against which the rescue efforts stood out sharply. So the rescue was not only a matter of holding a baby next to one’s skin. It was also about recognising what kind of action was possible and being able to take the proper steps quickly under pressure.

Some of the book’s most fascinating pages trace the development of the improvised systems that emerged during the months of crisis: blankets waved on a cliff to signal boats below; a mobile morgue for extra bodies; a pile of donated and sorted clothing waiting for people certain to need it. It was not just individual gestures but a complex amalgam of tools, methods, and relationships that saved so many lives.

There were three large vessels in the water that day under the control of the Hellenic Coast Guard: the seventy-five-foot Peter Henry Von Koss owned by the Norwegian Society for Sea Rescue, and two sixty-foot patrol boats based on Lesvos. All were charged with border protection primarily, though under maritime law they were obligated to assist with rescues at sea. As Carstensen writes:

Over the course of 2015, the HCG on Lesvos found itself on the frontlines of an ongoing humanitarian emergency for which it was poorly prepared. With a staff of only about forty for the whole island, the agency had responded to more than two thousand incidents of refugees in distress at sea. Their sleek, ultra-fast Lambro-57 patrol boats were excellent vessels for border control, but far from ideal for rescue operations… Even as tens of thousands of refugees crossed from Turkey to Lesvos each month, and accidents and drownings increased with the approaching winter weather, Athens didn’t add rescue vessels to the fleet, increase staffing, or provide crews with adequate CPR training and emergency medical supplies. Nor did the EU respond to requests from Greece for additional patrol boats and more thermal cameras.

Although the original reporting by Forensic Architecture suggested that European authorities failed to join the rescue, Carstensen found something different: the officers and crew made a genuine effort to help, but were hampered by inappropriate equipment, poor training, and, above all, confused judgment.

For instance, the captain of the Norwegian boat, worried about making political mistakes, failed to deploy life rafts because getting them into the water would require crossing the invisible sea border between Greece and Turkey.

Meanwhile, two Turkish fishermen who motored out into the strait as soon as they saw the large smuggler’s boat disintegrate made the opposite decision, negotiating to carry the refugees they rescued all the way to the Greek shore, despite fear of arrest and the confiscation of the vessels on which they depended for their livelihood. They did not go in blind or without consideration of the risk.

On the contrary, the Turks were independent and savvy advocates on the refugees’ behalf, using a combination of pleas and threats to win permission to approach the Greek island. What the highly credentialed, responsible, and well-meaning captain of the Peter Henry Von Koss, who represented official maritime authority, failed to manage, Emre Tmre and Ofuk Senol accomplished.

This contrast between state impotence and decentralised resilience presents a distinctly modern picture, one that can’t simply be projected backwards into a continuous history of displacement and persecution. European governance failures during the 2015 refugee crisis were the result of unjust laws and policies, of course, but Carstensen also allows us to see them in another light, as the result of fantasies, almost hallucinations, that blocked otherwise sane people from perceiving reality.

Damage to thinking ability is a known symptom of trauma. Some of the refugees can trace their own mistakes to cognitive blindness. Okba Bader was told by a smuggler that he would be travelling on a yacht with his own room and a porthole for the enjoyment of the view. This was absurd. Is there any smuggler in the world who would provide a comfortable passage in a private room on a cruise ship to a Syrian refugee? In retrospect, he is shocked by his foolishness. But trauma breaks the link between reality and its model. When all realistic paths are poisoned by terror, we choose unrealistic paths.

Jeanne Carstensen helps us see that the individuals responsible for carrying out government policy in 2015 had also lost their grip. It would be incorrect to talk about traumatised institutions or traumatised politics – these abstractions aren’t people and don’t merit compassion – but when the demands of reality break institutional models, the people assigned to enforce the rules get very stressed out; they just can’t think. The Spanish lifeguards, Greek nurses, local and international volunteers, and fishermen from both sides of the strait retained their cognitive and spiritual resources.

A Greek Tragedy was just published, but it already feels like an elegy. The contrast between local resilience and state blindness is a case study in the theory of modern systems. Whatever your take on modern state theory, you’re guaranteed to pick up the idea that rationalising bureaucratic governance can find itself absorbed in dangerous hallucinations even as it aims to organise the world in service to “the nation” or “the people” or “the masses.” However, the ascendant political philosophy of today has different features.

Our postmodern tech barons aren’t moved by visions of perfect order; instead, they express themselves in the jargon of online games and speculative risk. They speak of NPCs, non-playing characters whose opinions and emotions are presumed to be unreal because they are so predictable.

Virtue in this world means not being fooled, not being manipulated, and above all not being limited to a repertoire of common manoeuvres. The things that Stratis Valamios takes as proof of life — for instance, the instinct to mother — are recast as abject temptations, proven to be fake by the very fact that you share them with so many others. Only the unique perspective, the contrary bet, and the wilful rejection of solidarity count as evidence that a person exists.

With enough money, the consequences of this error can perhaps be concealed—for a while. Belief in the unreality of the world offers psychic immunity to the suffering around us. But it does not, in fact, make the world unreal.

Jeanne Carstensen’s astoundingly well-reported book suggests that when governance falters and we are plunged, metaphorically at least, into a borderless sea, rescue will depend on holding on to what we have in common.

Please support The Battleground. Subscribe to our free newsletter and make a donation to ensure our continued growth and independence.

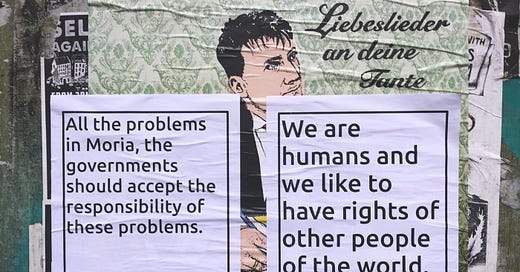

Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit. All rights reserved.